My Home Range

What’s that saying, you never forget your first love?

I’ve always considered the Uintas my home range. This is the place where I’ve had the most formative backcountry experiences. First time I ever backpacked with overnight gear, and woke up to the magic of an alpine sunrise. First time I ever watched a hungry trout chase a poorly presented dry fly, only to snap my rod back so fast it sent the tiny 6 inch brookie flying over my head. First time I ever felt the sheer terror of a lightning storm above treeline, the thunder exploding through my nylon tent wall while the floor filled with water because my seam-sealing job was absolutely terrible.

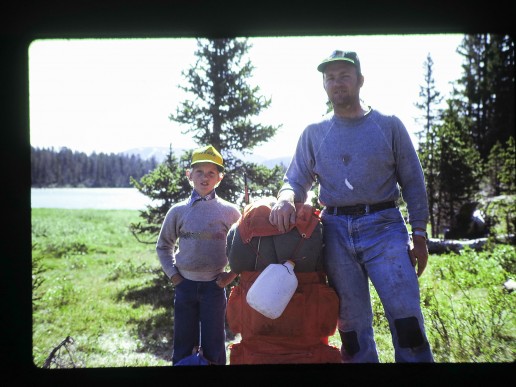

It’s also where I experienced the high of a “week-long” backpacking trip. For an 11 year old kid, decked out in denim jeans and cotton tee shirts, lugging a huge external frame pack with a ridiculous open cell mattress, it had all the potential for a serious suffer-fest.

Except it wasn’t. I loved waking up at high alpine lakes, watching the alpenglow crawl across the rooftop of Utah, and tinkering with my camera pretending I was a photographer. Year after year, I’d look forward to that week-long trip – even as a teenager it was the highlight of summer break.

While I can say the Uintas were my first, I’ve had something of an on-again, off-again relationship with them over the last 25 years. As I got older I started visiting other ranges. Bigger, more beautiful, more wild mountains. The Wind Rivers. The Sierras. Alaska. Nepal. And suddenly, my homey little Uintas didn’t feel so magnificent anymore. They just felt… tame?

In 2012, I was determined to respark my interest in the Uintas by traversing the classic Highline trail 85 miles from Leidy Peak to Highway 150. I’d spent over 50 nights in the Uinta backcountry, and never tied the range together in one single elegant landscape style trip. The Highline was the perfect trip.

Make no mistake, the Highline is incredible. But I couldn’t help but feel underwhelmed. The Uintas have so much more potential that isn’t realized on the Highline. The trail, (understandably) often takes the path of least resistance, instead of the most aesthetic.

The Uintas are a unique mountain range compared to its siblings in the Rockies – mainly because the crest runs predominantly east and west, rather than north and south. This gives the range two very distinct feelings – on the south side of the crest, the mountains feel more eroded, more gradual, more tame. Just across the crest, the range hides it’s most striking features. This is where glacial processes have carved towering cirques and steep tormented valleys of rotten unstable rock that the Uintas are famous for. But it also makes for much more difficult trail building, and in places where old shepherd trails existed, they’ve almost completely eroded away.

Immediately after my trip across the Highline Trail, I started scheming. What would the most aesthetic week-long route across the Uintas look like?

This trip would be about connecting 25 years of memories in the most beautiful line I could come up with.

What is a High Route?

The concept of a High Route is something that has been getting more traction in the lexicon of mainstream backpacking. (Is mainstream backpacking even a thing?) At it’s most basic, a high route is the concept of traversing a landscape using a patchwork of on and off trail navigation to create more elegant itineraries. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Roper’s Sierra High Route.

About the same time I contemplated a way to link up the Uintas, I also had completed a variation of what has come to be known as the Wind River High Route. I had pieced together options in the Winds from Nancy Pallister’s book, but Andrew Skurka and Alan Dixon had also published their own personal takes on the range, and the theme of high routes seemed to pick up a bit more momentum. Since then, Skurka, Dixon and others have published a number of other high routes.

Skurka has also written extensively about what a high route is, but ultimately it is still somewhat nebulous, which is exactly the point. To me, it’s all about connecting the dots across a landscape in an elegant way. How one defines “elegant” is totally up to the individual, and as such every route should be different than someone else.

I’ve debated about calling this a “high route” because of the obvious comparisons it will draw to other published routes. I could see an argument where the Uintas aren’t large enough with enough complex terrain, but the concept of a high route here does resonate. This is a more wild, more intense, and more scenic alternate to the Highline.

The Uinta High Route

In basic terms, the popular Highline Trail parallels the Uinta Crest, staying almost entirely on the south side. It only crosses to the north for one drainage – the West Fork of the Blacks Fork between Red Knob and Dead Horse Pass. It’s a short section, but almost always the most memorable part of that trail.

In contrast, the Uinta High Route uses a variety of off-trail passes to stay on the north side of the crest the entire way.

I like to describe the Uintas as a mountain range of crescendo. If traveling from east to west, the intensity and beauty of the trip builds with each day, finishing in the most stunning zones the range has to offer. In that context, the most logical place to start the trip is on the wilderness boundary at Spirit Lake, and to finish on the western boundary at Highway 150. In total, this variation is about 70 miles long, with 20,000 feet of vertical, and 8 off-trail passes.

This represents the wilderness core of the range, the best of the best. If your goal was to traverse the range in total, or you wanted an even bigger and more complete experience, you could start way farther east near Highway 191, and finish even farther west, perhaps at Smith and Morehouse.

By comparison to other published routes, the Uintas are probably not as physically demanding as options like Roper’s Sierra High Route, or trips that Skurka and Dixon have published. This doesn’t have as much vertical, and there isn’t as much overall mileage. The route finding, while off-trail and somewhat challenging in a few places on a micro scale, is overall probably not as difficult as other examples above because the off-trail sections are shorter and the range just simply isn’t as complex.

However, there are a few challenges that are still legit. A significant portion of the trip is above treeline where summer thunderstorms are common, and lightning is a real threat. You are above 10,000 feet for almost the entire trip, so altitude will have an impact. You should be comfortable off-trail and confident in your ability to navigate the dinner plate talus slopes the Uintas are famous for. And if you do cliff out, be prepared for rotten and terrifying rock.

The scale of the Uintas may not match those in the Winds or the Sierras, but the opportunity for adventure, solitude, and incredible backcountry landscapes do make for a very worthy objective.

My Idea of a Good Time

As I’ve gotten older (I’m 37 now) I’ve come to prioritize a few experiences in the backcountry more than others. One, I like to stay at or above tree-line as much as possible, because I simply think that’s where the magic happens. I love megascapes – where the views are massive and the sunsets go bonkers. My primary objective is to always camp at the most beautiful location possible, where I can photograph sunrise and sunset near the comfort (or shelter) of my camp. Chasing miles is no longer much of a priority. I can be just as happy doing a 20 mile day as I am 6, so long as the views are exceptional.

My second priority is to use my vacation time as efficiently as possible. Which means taking 5 days off work, adding two weekend days at each end for a grand total of 9 days. I find it takes me a couple days hiking before I really get into the peaceful backcountry rhythm where I totally relax, and that week-long duration is just about ideal.

That window also coincides with comfort level for total pack weight without feeling like it is work. 8 or 9 days usually means close to 20 pounds in just food. Add cameras, and I’m right about 35 pounds to start, which is pretty much perfect.

And my last priority is to make it challenging, but not a sufferfest. I want to feel a sense of accomplishment but not make it so hard I can’t get my wife or a few friends excited to join.

Within those parameters, this trip was about as good as it gets.

Spirit Lake to West Fork Beaver

I always seem to have a hard time recruiting folks to join me on longer backpacking trips. Turns out backpacking isn’t always the sexiest vacation to sell during the prime of summer. I had somehow convinced my wife Lindsey to join, but she was skeptical and wanted to have some more company. I made a pitch to our friends Kevin and Julie, trying to lure them to the Uintas for their first time. I told them it would probably suck, but if they brought enough whiskey it’d still be fun. We ran out of whiskey on Day 3.

Fortunately, the trip starts off super mellow, leaving the Spirit Lake trailhead and heading west. Out on the east end, the mountains tend to be pretty mellow, and there is at least a loose network of trails. However, because they are farther from Salt Lake, they seem to get a lot less visitors and are fairly overgrown and easy to lose. Makes for great solitude though, as Kevin and Julie found out when I went ahead to shoot a few photos and lost them entirely, which made for an hour of random wandering trying to find each other.

The scenery itself is pretty interesting, but nothing compared to what lies ahead. The walking is generally fast and painless, with some cruiser high alpine walking on Kabell Ridge and over the very scenic Thompson Pass, with big views to the north into Wyoming. On some maps there is a stretch of trail called the Highline “A” North Slope, but we’d be jumping off that very shortly heading south up to the headwaters of West Fork Beaver.

Once you are above 10,000 feet going up the West Fork Beaver, the scenery turns on in full force. Gilbert Peak towers above the drainage, and is the first of the Uinta 13ers along the route. To the east the dramatic Queens Cirque is also super photogenic. From here on out, off-trail passes are the norm, and we’d get our first taste of afternoon thunderstorms, as we’d try and time crossing between storm cells. Needless to say, it wasn’t a super effective strategy and we retreated twice before finally making it up and over into Henry’s Fork.

Henry’s Fork

The transition from Beaver to Henry’s Fork is rather dramatic, not just because the scenery is amazing but also because Henry’s Fork is the primary corridor to King’s Peak, the Utah state high point. The basin is large and expansive by Uinta standards, so it’s pretty easy to disperse and find solitude. But it also makes for prime grazing for sheep, and there is often a semi-permanent shepherd camp right at treeline, as well as a large herd of sheep roaming around.

13,000 foot peaks ring the entire basin, and make for amazing sunrises and sunsets. We found a nice little spot in the meadow above treeline and made camp, not realizing that the sheep herders were moving their animals in our general direction later that night. Around sunset, a very protective pyrynees sheepdog made its way up to our camp, and made it pretty clear he wasn’t very happy we were hanging around. After 30 minutes of being harassed, and trying to decide if we needed to up and move camp, the dog and its sheep retreated a few hundred yards away.

As we woke up the next morning, we found the herd between our camp and the pass we needed to cross. We decided not to tempt the massive dogs, and took the long way around to avoid them. It’s one time in the Uintas I wish I had carried bear-spray, just in case. Instead I kept a handful of salami close by, thinking I could throw it to the dog and at least distract him for a second. It wouldn’t have done a damn thing, but at least it made Lindsey feel better. Ha.

There are multiple options for crossing from Henry’s Fork into the Smith’s Fork and Red Castle Lakes, and depending on snow conditions you might have to try a few options. In heavy snow years like 2019, the passes between Henry’s Fork and Middle Basin all have potential to hold significant snow late into the year, possibly even through the entire season.

Red Castle and Smiths Fork

Red Castle may be the single most iconic peak in the entire Uintas. At 12,338 it’s nowhere near the tallest peak, but you wouldn’t necessarily know that when you are at its base, there is almost 2,000 feet of sheer prominence from Lower Red Castle Lake to the summit. The views are outstanding, and on the weekends this is another super popular zone. If solitude is your primary goal, it’s pretty easy to find equally impressive views near Smiths Fork Pass Lake, East Red Castle, or even west of Red Castle. The photos won’t be the cliche view from Lower Red Castle, but they are equally stunning, and come with a lot more solitude.

This is also prime moose habitat, and every time I’ve been in Smith’s Fork I seem to see a few. The only exception is when the sheep are here, and everything seems to disappear. It’s also very common to see mountain goats in these drainages. While seeing a mountain goat is pretty cool, they are not native in these mountains. The native ungulates are bighorn, but because of the diseases introduced by domestic sheep, the native populations have been wiped out. Mountain goats were introduced to satisfy the appetites of hunters. Keep an eye on the vertical cliffs and ridges and they are fairly easy to spot with their bright white coats.

Little and East Forks Blacks Fork

If you were charting out “must see” drainages, Henry’s Fork and Smith’s Fork have to be near the top of the list. But heading west from Red Castle, you can make the argument that Oweep is the more scenic route, while the East Fork Blacks Forks drainages are less so. There are other pros and cons to each route. Oweep is stunning with some killer walking above treeline, and it leads to some very cool off-trail zones to camp. It also only requires crossing one off-trail pass above Red Castle, where staying on the north side of the crest requires crossing two, the second of which is somewhat obscure and requires patience to locate.

Jumping over the ridge from Smiths Fork to the Little East Fork is fairly straighforward, and puts you into a seldom visited drainage compared to Red Castle. There are no large lakes and meadows in the Little East Fork, so it tends to keep some of the bigger groups from venturing into it.

The crossing from Little East Fork into the East Fork Blacks Fork is a little more challenging, especially in high snow years. If the snow is threatening, another option is to just go south over Squaw Pass into Oweep Basin, and then reconnect with the north slope route at Red Knob Pass.

These are some of my favorite drainages in the entire range, primarily because they feel more remote, they get less livestock grazing, and the views are outstanding. If you are also bagging 13ers along the way, this is the route to take with better access to Lovenia, Wasatch, and Tokewanna.

Oweep Basin (Alternate)

On this trip, we decided to take Oweep Basin. This option means going off-trail above Red Castle Lake and joining back up with the Highline Trail near Porcupine Pass. I would argue that Oweep is a bit more scenic hike than the East Fork Drainages, and if you needed to make miles or were looking for a much less strenuous route between Red Castle and Red Knob, this would be a solid choice.

Oweep itself is pretty rad, as the south side is largely unbroken cliff band that extends a few miles. The walking is almost all above treeline all the way to Lambert Meadow, and the views into the upper Lake Fork are outstanding. The south face of Lovenia is also rather photogenic, and when there aren’t sheep in the Upper Lake Fork, it makes for fantastic photos. This entire stretch is on the Highline Trail, but it is one of the more remote stretches so it doesn’t seem to get a lot of pressure.

West Fork Blacks Fork

The Highline Trail dips into the north slope drainages exactly one time, between Red Knob and Deadhorse Pass. If coming cross country from the East Fork Blacks Fork, the most simple route connects with the Highline at Red Knob, and descends via the Highline to Dead Horse Pass. Other off-trail passes exist close by, but because you are so close it would be a bit of stunt to avoid the Highline just for the sake of avoiding it entirely.

This is arguably the most intense stretch of the entire Highline, and Deadhorse Pass is notorious for being steep, exposed, and holding a ton of snow in big snow years. Fortunately, the High Route does not cross at Deadhorse, but instead crosses west over Allsop Pass.

There are remnants of an old constructed trail on Allsop on the east side, but the west side is far less obvious, any trail that may have once existed is pretty well gone. You have two choices. One is to directly descend the very steep couloir that bisects the cliff bands. Or the second is to traverse to the north along the ridge, and pick your way down another classic Uinta talus slope. The direct coloir is faster and easier, but it looks far more intimidating. And in high snow years, it might be impassable without an axe and crampons.

Another fun piece of random trivia: Allsop Pass is a watershed divide in the Uintas. All the water draining from the Blacks Forks drainages goes into the Green River, to the Colorado, and eventually the Gulf of California. Everything west drains into the Bear River, which is the largest tributary of the Great Salt Lake, which is completely landlocked and has no outflow.

Allsop Pass and the Mystery of Eric Robinson

In 2011, the Uintas experienced an above average snowfall. Deadhorse in particular held snow well into August, and it caused trouble for aspiring Highline hikers. In late July, an Australian man named Eric Robinson set out to hike the Highline, but he missed his check-in date a week later.

Massive search and rescue operations lasted several weeks, and flyers were pasted on every trailhead. Despite the incredible efforts of search and rescue teams and many volunteers, very few clues to his fate ever surfaced.

The next clue to his disappearance would not show up until 5 years later, the day we crossed Allsop Pass in August 2016. As we made our way along the ridge above Allsop Lake, we could hear another group at the base of the cliffs below us. They had just found Robinson’s backpack, and a few remains. We had no idea what had happened until the next morning, when they came into our camp and explained what they had found. I immediately remembered the search for Robinson in 2011, and using my inReach, I texted the sheriff’s office to start a search and rescue recovery.

While I am not sure exactly what caused Robinson’s death, I think one plausible scenario is that he arrived at the base of Deadhorse Pass in 2011, and saw how much snow there was. Perhaps he wanted to avoid Deadhorse altogether and began looking for alternatives, or given the conditions he may have mistaken Allsop Pass for Deadhorse Pass. If comparing the two options from Deadhorse Lake, Allsop does looks more inviting, as it is much less steep and unlikely to hold snow on that aspect. But you cannot see the the difficult routefinding until you are on top. Either by choice or by accident, Robinson ended up crossing Allsop pass, where the ridge is a convex slope that slowly rolls over before becoming vertical cliffs. In the absence of an obvious trail, it would make sense to probe the slope to find a weakness to make it down to the lake. Robinson was found at the base of these cliffs, almost certainly because of a fall.

The thing that sticks with me the most is how close Robinson was to relatively high-traffic areas of the Uintas. Allsop Pass is between two very popular camping destinations in Deadhorse and Allsop, but at just a mile off-trail, he was never found. It also illustrates the risks associated with both high snow years, and off-trail navigation.

Left and Right Hand Forks

These two drainages are commonly referred to as Allsop and Priord, for the lakes at the tops of the drainages. On topo maps, they are labeled the Left and Right Hand forks of the East Fork of the Bear River. Quite a mouthful.

One of the most photogenic ridges in the entire range splits the two forks, with Yard Peak on the south, and the Cathedral on the north. Incredible campsites can be found in both drainages, with Allsop generally getting more pressure than Priord. This is a very popular zone, and it’s not uncommon to see horsepacking camps in the area, as access from the East Fork of the Bear River Trailhead is pretty convenient. It’s also very common to share Allsop with cattle, and complaints of it being “cowed out” are pretty apt. The lake itself is surrounded by a meadow and some prime grazing zones, so be prepared.

You are probably sensing a theme by now about my opinion of livestock in the Uintas. I understand the issue has many layers and the designation of the Wilderness in 1984 allowed for legal grazing to continue, but the damage done by grazing is the single biggest impact to these areas. I do hope that one day the actual wilderness boundaries will exclude livestock so these areas can recover, at least as close to their natural state as possible.

As the route continues west, the intensity of the off-trail passes increase as well. Years ago I had probed a few of the passes between Allsop and Priord hoping to find a reasonable way to make a lollipop loop out of the two, when I discovered the remains of an old ranching trail that had been built. Time has nearly wiped whatever is left of the route completely away, but a few stretches of it can be found here and there. I’ve done that route a few times now, and every single time I seem to take a different variation, depending on conditions. A few years ago I also discovered it is marked on multiple different maps as an actual trail, though you’d have a hard time calling it that today. It is, however, one of the coolest pieces of the puzzle in linking up the North Slope drainages. You can read more about that loop here.

If the pass between Allsop and Priord is mildly difficult, the route between Priord and Amethyst is significantly worse. I had heard rumors from a fellow backpacker years ago that he once saw a man on horseback on the saddle between the two, but having scouted multiple options to get between those drainages, I can pretty confidently say that rumor is impossible.

Ascending from Priord is not particularly difficult, but it is very steep, a bit loose up top, and picking the right saddle can be a chore. Descending into Amethyst, however, is a very delicate affair. Picking the right line is paramount, even being off by 50 yards will lead you to being cliffed out or in scary technical terrain with horrible rock. That said, with a little careful routefinding, it is entirely possible to descend in Class II terrain (albeit very loose!). Once down, it’s a good place to chill and breathe a sigh of relief.

Amethyst and Middle Basin

In true crescendo, the Uintas reach their scenic peak on the final day.

Amethyst Lake, tucked into an incredible cirque ringed by cliffs from Ostler and Lamotte Peaks, is in my opinion the single most stunning lake in the entire range. Good luck capturing a photo that can truly do the place justice, the views are 360 degrees in every direction, and a wide angle just doesn’t seem to convey the scale of the place well at all.

Not surprisingly, Amethyst does see a fair share of crowds, as it is accessed from one of the trail heads closest to Salt Lake. Every alpine camp in the Uintas should be as minimal impact as possible, but it is especially important at treeline. Some lakes will allow fires, and some do not. As a general rule I try not to have any campfires where wood is at a premium. Years of campfires have reduced the wood supply to almost zero in many of these places. Consider skipping the campfire when at treeline, which makes a minimal impact camp.

There are multiple route options from Amethyst to Middle Basin, including tagging the very cool summit of Ostler Peak – but you are also very close to an actual trail, so just jumping on the Ostler Fork trail, and wrapping around onto the Stillwater Fork is still probably the most appropriate option.

Where Amethyst Lake is more intimate, tucked into a stunning cirque, Middle Basin is more expansive, with massive views in every direction. Middle Basin is one of the largest basins on the North Slope, but it is still surrounded on all sides by stunning peaks like Hayden and Agassiz. There are countless lakes, cascades, and meadows to explore. The views are outstanding, and some of the most ridiculous sunsets I’ve ever experienced in the Uintas have been in Middle Basin.

Saving the Best for Last

If the best scenery comes last, so does the most challenging pass. Or, at least, it can be if you aren’t careful.

Sometimes called the Hayden Pass shortcut, or the Middle Basin shortcut, this pass crossing will take you from Middle Basin back to Highway 150 at the Hayden Pass Trailhead – the end (or beginning) of the Uinta Highline Trailhead. When approaching the pass from the trailhead at Hayden Pass, the route is far more easy to see and pick a clean line. Coming from Middle Basin, the slope is the classic Uinta convex slope where you can’t quite see what is below you as it slowly rolls away. This can lead to some pretty tedious routefinding as you try to find the right weakness to descend.

That said, there are a couple options. One is a short 10 or 15 foot downclimb in a pretty secure off-width chimney that probably goes at around 4th class or super easy class 5. You can pass packs here and help spot each other and it is manageable. A little farther to the south there is a series of ledges that you can negotiate, with the biggest drop being about 6 feet. It’s easy to spot from below, more difficult from above. That section I consider class 3.

This route is often used to summit Hayden Peak from Highway 150, so there is a pretty good social trail along the ridge between the road and the pass. Once you negotiate the cliff band, the hard work is done. Below you will hear the sounds of traffic and crowds more people hanging out at any of a number of roadside lakes off the Mirror Lake Highway.

The transition back to the land of the living is abrupt, and while I walked the last few miles back to a luke-warm beer at the truck, I wondered if I had just answered the question that sparked this whole trip in the first place. “Was this the most beautiful line I could come up with?”

Of course, the question itself is absurd. There is no such thing, and I already have a few ideas for the next trip.

But this wasn’t just about a beautiful line; it was about re-igniting that feeling I had 25 years ago, experiencing the magic of a week in these mountains again for the first time.

Dan, Excellent! Thanks for posting this! I have been hoping for more info on your trip since I first heard about it. In the article right after “What is a High Route” you have a photo of three standing on a high rocky cliff point, I’d love to know the location this pic was taken, if you dont mind sharing. Thanks

That’s Thompson Pass.

I clicked into this report after just reading through your Wind River write-up. All I have to say is, Bummer. I’m disappointed I didn’t make it into the background of any shot through Oweep there before we crossed paths with you. Oh well. By the way, what’s your water filtration system looking like these days after that blowout with your Sawyer bag?

This is an incredible route you pieced together. When I camped at Allsop a few years ago, I surveyed the ridge above to the east wondering where exactly the descent off the ridge was that those few like you who’ve done it have done so. In that same weekend trip up there, we did make it up the ridge over to Priord’s drainage and probed a few spots along the saddle until we found the clearest way over. I remember those views up there being as spectacular as any I’ve ever enjoyed up there. I’ve still yet to make it up to Amethyst, instead opting to go up into Middle Basin both times I’ve gone up Stillwater. You now have me convinced it really is worth a visit up into Amethyst, crowds and all. I might just try sneak up there for a night in the next week or two. I’m also keen to scout out the pass between Priord and Rock Creek at some point.

In the mean time…I’m still really struggling with what I want to do for my 4 day birthday trip with my wife coming up. Probably still going to go for the “Kings Castle” lolli-loop of China Meadow TH>Henry Fork>Kings Peak>East Red Castle/Red Castle/Smith Fork>China Meadow, ensuring visits to many of the waterfalls along that route and a probable romp up to that pass between Upper Red Castle and Oweep just to show that view off to my wife, if not all the way back up for a return to Wilson Peak, and perhaps a bit of time for fishing a night or two. It’d be a nice healthy mix of old and new for me, yet everything new for my wife. But for twice the drive up to Big Sandy in Wyoming, rather than try to hook Cathedral Lakes into a route through the Towers, I’m now thinking of another impressive looking Wind River route that would probably be more plausible over 4 days with more bang for the buck: Big Sandy>Pyramid Lake/Desolation Valley>Hailey Pass>Baptiste Lake>Ranger Park>Valentine Lake>Lizard Head Plateau>Papoose Lake (maybe)>Cirque of the Towers>Big Sandy where everything along there would be all new for both of us. While still keen to do the former, the latter is now high on my list for something to consider to next year if we don’t leave the fate of our journey up to a coin toss. Would be nice if we could split ourselves in half and do both trips at once.

Haha, sorry no photos. We used a Sawyer Squeeze and a Mini on this trip. I’ve decided I’ll never use a mini again, it’s just too prone to clogging and failure. I actually have carried a regular squeeze a few times since. But almost always back to just carrying aquamira. It’s lightest and most fail-proof. But it does take a half hour.

[…] 5-7 day trips, where total pack weights will be below 35 lbs. This will be ideal for trips like the Uinta High Route or Wind River High […]

Thanks for the nice write up! Thinking about giving it a go next week.

A couple question on logistics:

1) Are there any issues with leaving food in cars at the TH for multi-day trips?

2) For those with only one vehicle, is there any good way to get back to Spirit Lake after hiking west? I assume thumbing it is an option although not great this year.

Thanks!